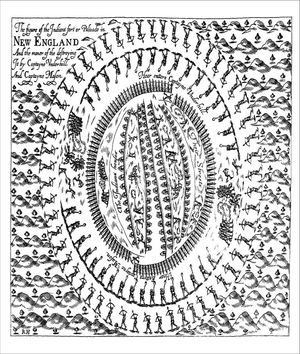

© Republic of Lakotah Laura Elliff Republic of Lakotah Sun, 22 Nov 2009 00:00 CST Is All That Turkey and Stuffing a Celebration of Genocide? Thanksgiving is a holiday where families gather to share stories, football games are watched on television and a big feast is served. It is also the time of the month when people talk about Native Americans. But does one ever wonder why we celebrate this national holiday? Why does everyone give thanks? History is never simple. The standard history of Thanksgiving tells us that the "Pilgrims and Indians" feasted for three days, right? Most Americans believe that there was some magnificent bountiful harvest. In the Thanksgiving story, are the "Indians" even acknowledged by a tribe? No, because everyone assumes "Indians" are the same. So, who were these Indians in 1621? In 1620, Pilgrims arrived on the Mayflower naming the land Plymouth Rock. One fact that is always hidden is that the village was already named Patuxet and the Wampanoag Indians lived there for thousands of years. To many Americans, Plymouth Rock is a symbol. Sad but true many people assume, "It is the rock on which our nation began." In 1621, Pilgrims did have a feast but it was not repeated years thereafter. So, it wasn't the beginning of a Thanksgiving tradition nor did Pilgrims call it a Thanksgiving feast. Pilgrims perceived Indians in relation to the Devil and the only reason why they were invited to that feast was for the purpose of negotiating a treaty that would secure the lands for the Pilgrims. The reason why we have so many myths about Thanksgiving is that it is an invented tradition. It is based more on fiction than fact. So, what truth ought to be taught? In 1637, the official Thanksgiving holiday we know today came into existence. (Some people argue it formally came into existence during the Civil War, in 1863, when President Lincoln proclaimed it, which also was the same year he had 38 Sioux hung on Christmas Eve.) William Newell, a Penobscot Indian and former chair of the anthropology department of the University of Connecticut, claims that the first Thanksgiving was not "a festive gathering of Indians and Pilgrims, but rather a celebration of the massacre of 700 Pequot men, women and children." In 1637, the Pequot tribe of Connecticut gathered for the annual Green Corn Dance ceremony. Mercenaries of the English and Dutch attacked and surrounded the village; burning down everything and shooting whomever try to escape. The next day, Newell notes, the Governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony declared: "A day of Thanksgiving, thanking God that they had eliminated over 700 men, women and children." It was signed into law that, "This day forth shall be a day of celebration and thanksgiving for subduing the Pequots." Most Americans believe Thanksgiving was this wonderful dinner and harvest celebration. The truth is the "Thanksgiving dinner" was invented both to instill a false pride in Americans and to cover up the massacre. Was Thanksgiving really a massacre of 700 "Indians"? The present Thanksgiving may be a mixture of the 1621 three-day feast and the "Thanksgiving" proclaimed after the 1637 Pequot massacre. So next time you see the annual "Pilgrim and Indian display" in a shopping window or history about other massacres of Native Americans, think of the hurt and disrespect Native Americans feel. Thanksgiving is observed as a day of sorrow rather than a celebration. This year at Thanksgiving dinner, ponder why you are giving thanks. William Bradford, in his famous History of the Plymouth Plantation, celebrated the Pequot massacre:"Those that scraped the fire were slaine with the sword; some hewed to peeces, others rune throw with their rapiers, so as they were quickly dispatchte, and very few escapted. It was conceived they thus destroyed about 400 at this time. It was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fyer, and the streams of blood quenching the same, and horrible was the stincke and sente there of, but the victory seemed a sweete sacrifice, and they gave the prayers thereof to God, who had wrought so wonderfully for them, thus to inclose their enemise in their hands, and give them so speedy a victory over so proud and insulting an enimie."The Pequot massacre came after the colonists, angry at the murder of an English trader suspected by the Pequots of kidnapping children, sought revenge. rather than fighting the dangerous Pequot warriors, John Mason and John Underhill led a group of colonists and Native allies to the Indian fort in Mystic, and killed the old men, women, and children who were there. Those who escaped were later hunted down. The Pequot tribe numbered 8,000 when the Pilgrims arrived, but disease had brought their numbers down to 1,500 by 1637. The Pequot "War" killed all but a handful of remaining members of the tribe. An illustration from John Underhill's News from America, depicting how the village was surrounded.

Proud of their accomplishments, Underhill wrote a book, depicted the burning of the village, and even made an illustration showing how they surrounded the village to kill all within it. Laura Elliff is Vice President of Native American Student Association.

1 Comment

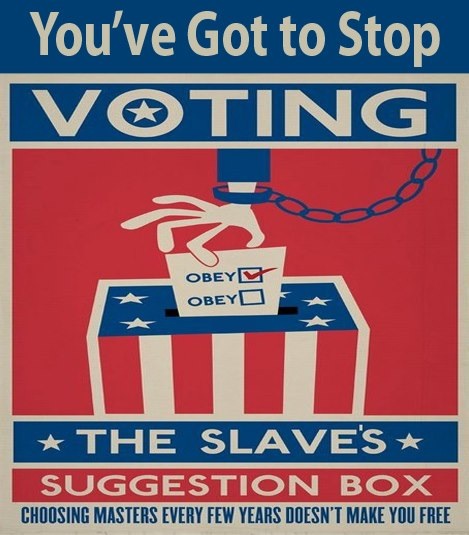

Photograph: Brian Ulrich BY JEFFREY KAPLAN Published in the May/June 2008 issue of Orion magazine PRIVATE CARS WERE RELATIVELY SCARCE in 1919 and horse-drawn conveyances were still common. In residential districts, electric streetlights had not yet replaced many of the old gaslights. And within the home, electricity remained largely a luxury item for the wealthy. Just ten years later things looked very different. Cars dominated the streets and most urban homes had electric lights, electric flat irons, and vacuum cleaners. In upper-middle-class houses, washing machines, refrigerators, toasters, curling irons, percolators, heating pads, and popcorn poppers were becoming commonplace. And although the first commercial radio station didn’t begin broadcasting until 1920, the American public, with an adult population of about 122 million people, bought 4,438,000 radios in the year 1929 alone. But despite the apparent tidal wave of new consumer goods and what appeared to be a healthy appetite for their consumption among the well-to-do, industrialists were worried. They feared that the frugal habits maintained by most American families would be difficult to break. Perhaps even more threatening was the fact that the industrial capacity for turning out goods seemed to be increasing at a pace greater than people’s sense that they needed them. It was this latter concern that led Charles Kettering, director of General Motors Research, to write a 1929 magazine article called “Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied.” He wasn’t suggesting that manufacturers produce shoddy products. Along with many of his corporate cohorts, he was defining a strategic shift for American industry—from fulfilling basic human needs to creating new ones. In a 1927 interview with the magazine Nation’s Business, Secretary of Labor James J. Davis provided some numbers to illustrate a problem that the New York Times called “need saturation.” Davis noted that “the textile mills of this country can produce all the cloth needed in six months’ operation each year” and that 14 percent of the American shoe factories could produce a year’s supply of footwear. The magazine went on to suggest, “It may be that the world’s needs ultimately will be produced by three days’ work a week.” Business leaders were less than enthusiastic about the prospect of a society no longer centered on the production of goods. For them, the new “labor-saving” machinery presented not a vision of liberation but a threat to their position at the center of power. John E. Edgerton, president of the National Association of Manufacturers, typified their response when he declared: “I am for everything that will make work happier but against everything that will further subordinate its importance. The emphasis should be put on work—more work and better work.” “Nothing,” he claimed, “breeds radicalism more than unhappiness unless it is leisure.” By the late 1920s, America’s business and political elite had found a way to defuse the dual threat of stagnating economic growth and a radicalized working class in what one industrial consultant called “the gospel of consumption”—the notion that people could be convinced that however much they have, it isn’t enough. President Herbert Hoover’s 1929 Committee on Recent Economic Changes observed in glowing terms the results: “By advertising and other promotional devices . . . a measurable pull on production has been created which releases capital otherwise tied up.” They celebrated the conceptual breakthrough: “Economically we have a boundless field before us; that there are new wants which will make way endlessly for newer wants, as fast as they are satisfied.” Today “work and more work” is the accepted way of doing things. If anything, improvements to the labor-saving machinery since the 1920s have intensified the trend. Machines can save labor, but only if they go idle when we possess enough of what they can produce. In other words, the machinery offers us an opportunity to work less, an opportunity that as a society we have chosen not to take. Instead, we have allowed the owners of those machines to define their purpose: not reduction of labor, but “higher productivity”—and with it the imperative to consume virtually everything that the machinery can possibly produce. FROM THE EARLIEST DAYS of the Age of Consumerism there were critics. One of the most influential was Arthur Dahlberg, whose 1932 book Jobs, Machines, and Capitalism was well known to policymakers and elected officials in Washington. Dahlberg declared that “failure to shorten the length of the working day . . . is the primary cause of our rationing of opportunity, our excess industrial plant, our enormous wastes of competition, our high pressure advertising, [and] our economic imperialism.” Since much of what industry produced was no longer aimed at satisfying human physical needs, a four-hour workday, he claimed, was necessary to prevent society from becoming disastrously materialistic. “By not shortening the working day when all the wood is in,” he suggested, the profit motive becomes “both the creator and satisfier of spiritual needs.” For when the profit motive can turn nowhere else, “it wraps our soap in pretty boxes and tries to convince us that that is solace to our souls.” There was, for a time, a visionary alternative. In 1930 Kellogg Company, the world’s leading producer of ready-to-eat cereal, announced that all of its nearly fifteen hundred workers would move from an eight-hour to a six-hour workday. Company president Lewis Brown and owner W. K. Kellogg noted that if the company ran “four six-hour shifts . . . instead of three eight-hour shifts, this will give work and paychecks to the heads of three hundred more families in Battle Creek.” This was welcome news to workers at a time when the country was rapidly descending into the Great Depression. But as Benjamin Hunnicutt explains in his book Kellogg’s Six-Hour Day, Brown and Kellogg wanted to do more than save jobs. They hoped to show that the “free exchange of goods, services, and labor in the free market would not have to mean mindless consumerism or eternal exploitation of people and natural resources.” Instead “workers would be liberated by increasingly higher wages and shorter hours for the final freedom promised by the Declaration of Independence—the pursuit of happiness.” To be sure, Kellogg did not intend to stop making a profit. But the company leaders argued that men and women would work more efficiently on shorter shifts, and with more people employed, the overall purchasing power of the community would increase, thus allowing for more purchases of goods, including cereals. A shorter workday did entail a cut in overall pay for workers. But Kellogg raised the hourly rate to partially offset the loss and provided for production bonuses to encourage people to work hard. The company eliminated time off for lunch, assuming that workers would rather work their shorter shift and leave as soon as possible. In a “personal letter” to employees, Brown pointed to the “mental income” of “the enjoyment of the surroundings of your home, the place you work, your neighbors, the other pleasures you have [that are] harder to translate into dollars and cents.” Greater leisure, he hoped, would lead to “higher standards in school and civic . . . life” that would benefit the company by allowing it to “draw its workers from a community where good homes predominate.” It was an attractive vision, and it worked. Not only did Kellogg prosper, but journalists from magazines such as Forbes andBusinessWeek reported that the great majority of company employees embraced the shorter workday. One reporter described “a lot of gardening and community beautification, athletics and hobbies . . . libraries well patronized and the mental background of these fortunate workers . . . becoming richer.” A U.S. Department of Labor survey taken at the time, as well as interviews Hunnicutt conducted with former workers, confirm this picture. The government interviewers noted that “little dissatisfaction with lower earnings resulting from the decrease in hours was expressed, although in the majority of cases very real decreases had resulted.” One man spoke of “more time at home with the family.” Another remembered: “I could go home and have time to work in my garden.” A woman noted that the six-hour shift allowed her husband to “be with 4 boys at ages it was important.” Those extra hours away from work also enabled some people to accomplish things that they might never have been able to do otherwise. Hunnicutt describes how at the end of her interview an eighty-year-old woman began talking about ping-pong. “We’d get together. We had a ping-pong table and all my relatives would come for dinner and things and we’d all play ping-pong by the hour.” Eventually she went on to win the state championship. Many women used the extra time for housework. But even then, they often chose work that drew in the entire family, such as canning. One recalled how canning food at home became “a family project” that “we all enjoyed,” including her sons, who “opened up to talk freely.” As Hunnicutt puts it, canning became the “medium for something more important than preserving food. Stories, jokes, teasing, quarreling, practical instruction, songs, griefs, and problems were shared. The modern discipline of alienated work was left behind for an older . . . more convivial kind of working together.” This was the stuff of a human ecology in which thousands of small, almost invisible, interactions between family members, friends, and neighbors create an intricate structure that supports social life in much the same way as topsoil supports our biological existence. When we allow either one to become impoverished, whether out of greed or intemperance, we put our long-term survival at risk. Our modern predicament is a case in point. By 2005 per capita household spending (in inflation-adjusted dollars) was twelve times what it had been in 1929, while per capita spending for durable goods—the big stuff such as cars and appliances—was thirty-two times higher. Meanwhile, by 2000 the average married couple with children was working almost five hundred hours a year more than in 1979. And according to reports by the Federal Reserve Bank in 2004 and 2005, over 40 percent of American families spend more than they earn. The average household carries $18,654 in debt, not including home-mortgage debt, and the ratio of household debt to income is at record levels, having roughly doubled over the last two decades. We are quite literally working ourselves into a frenzy just so we can consume all that our machines can produce. Yet we could work and spend a lot less and still live quite comfortably. By 1991 the amount of goods and services produced for each hour of labor was double what it had been in 1948. By 2006 that figure had risen another 30 percent. In other words, if as a society we made a collective decision to get by on the amount we produced and consumed seventeen years ago, we could cut back from the standard forty-hour week to 5.3 hours per day—or 2.7 hours if we were willing to return to the 1948 level. We were already the richest country on the planet in 1948 and most of the world has not yet caught up to where we were then. Rather than realizing the enriched social life that Kellogg’s vision offered us, we have impoverished our human communities with a form of materialism that leaves us in relative isolation from family, friends, and neighbors. We simply don’t have time for them. Unlike our great-grandparents who passed the time, we spend it. An outside observer might conclude that we are in the grip of some strange curse, like a modern-day King Midas whose touch turns everything into a product built around a microchip. Of course not everybody has been able to take part in the buying spree on equal terms. Millions of Americans work long hours at poverty wages while many others can find no work at all. However, as advertisers well know, poverty does not render one immune to the gospel of consumption. Meanwhile, the influence of the gospel has spread far beyond the land of its origin. Most of the clothes, video players, furniture, toys, and other goods Americans buy today are made in distant countries, often by underpaid people working in sweatshop conditions. The raw material for many of those products comes from clearcutting or strip mining or other disastrous means of extraction. Here at home, business activity is centered on designing those products, financing their manufacture, marketing them—and counting the profits. KELLOGG’S VISION, DESPITE ITS POPULARITY with his employees, had little support among his fellow business leaders. But Dahlberg’s book had a major influence on Senator (and future Supreme Court justice) Hugo Black who, in 1933, introduced legislation requiring a thirty-hour workweek. Although Roosevelt at first appeared to support Black’s bill, he soon sided with the majority of businessmen who opposed it. Instead, Roosevelt went on to launch a series of policy initiatives that led to the forty-hour standard that we more or less observe today. By the time the Black bill came before Congress, the prophets of the gospel of consumption had been developing their tactics and techniques for at least a decade. However, as the Great Depression deepened, the public mood was uncertain, at best, about the proper role of the large corporation. Labor unions were gaining in both public support and legal legitimacy, and the Roosevelt administration, under its New Deal program, was implementing government regulation of industry on an unprecedented scale. Many corporate leaders saw the New Deal as a serious threat. James A. Emery, general counsel for the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), issued a “call to arms” against the “shackles of irrational regulation” and the “back-breaking burdens of taxation,” characterizing the New Deal doctrines as “alien invaders of our national thought.” In response, the industrial elite represented by NAM, including General Motors, the big steel companies, General Foods, DuPont, and others, decided to create their own propaganda. An internal NAM memo called for “re-selling all of the individual Joe Doakes on the advantages and benefits he enjoys under a competitive economy.” NAM launched a massive public relations campaign it called the “American Way.” As the minutes of a NAM meeting described it, the purpose of the campaign was to link “free enterprise in the public consciousness with free speech, free press and free religion as integral parts of democracy.” Consumption was not only the linchpin of the campaign; it was also recast in political terms. A campaign booklet put out by the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency told readers that under “private capitalism, the Consumer, the Citizen is boss,” and “he doesn’t have to wait for election day to vote or for the Court to convene before handing down his verdict. The consumer ‘votes’ each time he buys one article and rejects another.” According to Edward Bernays, one of the founders of the field of public relations and a principal architect of the American Way, the choices available in the polling booth are akin to those at the department store; both should consist of a limited set of offerings that are carefully determined by what Bernays called an “invisible government” of public-relations experts and advertisers working on behalf of business leaders. Bernays claimed that in a “democratic society” we are and should be “governed, our minds . . . molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.” NAM formed a national network of groups to ensure that the booklet from J. Walter Thompson and similar material appeared in libraries and school curricula across the country. The campaign also placed favorable articles in newspapers (often citing “independent” scholars who were paid secretly) and created popular magazines and film shorts directed to children and adults with such titles as “Building Better Americans,” “The Business of America’s People Is Selling,” and “America Marching On.” Perhaps the biggest public relations success for the American Way campaign was the 1939 New York World’s Fair. The fair’s director of public relations called it “the greatest public relations program in industrial history,” one that would battle what he called the “New Deal propaganda.” The fair’s motto was “Building the World of Tomorrow,” and it was indeed a forum in which American corporations literally modeled the future they were determined to create. The most famous of the exhibits was General Motors’ 35,000-square-foot Futurama, where visitors toured Democracity, a metropolis of multilane highways that took its citizens from their countryside homes to their jobs in the skyscraper-packed central city. For all of its intensity and spectacle, the campaign for the American Way did not create immediate, widespread, enthusiastic support for American corporations or the corporate vision of the future. But it did lay the ideological groundwork for changes that came after the Second World War, changes that established what is still commonly called our post-war society. The war had put people back to work in numbers that the New Deal had never approached, and there was considerable fear that unemployment would return when the war ended. Kellogg workers had been working forty-eight-hour weeks during the war and the majority of them were ready to return to a six-hour day and thirty-hour week. Most of them were able to do so, for a while. But W. K. Kellogg and Lewis Brown had turned the company over to new managers in 1937. The new managers saw only costs and no benefits to the six-hour day, and almost immediately after the end of the war they began a campaign to undermine shorter hours. Management offered workers a tempting set of financial incentives if they would accept an eight-hour day. Yet in a vote taken in 1946, 77 percent of the men and 87 percent of the women wanted to return to a thirty-hour week rather than a forty-hour one. In making that choice, they also chose a fairly dramatic drop in earnings from artificially high wartime levels. The company responded with a strategy of attrition, offering special deals on a department-by-department basis where eight hours had pockets of support, typically among highly skilled male workers. In the culture of a post-war, post-Depression U.S., that strategy was largely successful. But not everyone went along. Within Kellogg there was a substantial, albeit slowly dwindling group of people Hunnicutt calls the “mavericks,” who resisted longer work hours. They clustered in a few departments that had managed to preserve the six-hour day until the company eliminated it once and for all in 1985. The mavericks rejected the claims made by the company, the union, and many of their co-workers that the extra money they could earn on an eight-hour shift was worth it. Despite the enormous difference in societal wealth between the 1930s and the 1980s, the language the mavericks used to explain their preference for a six-hour workday was almost identical to that used by Kellogg workers fifty years earlier. One woman, worried about the long hours worked by her son, said, “He has no time to live, to visit and spend time with his family, and to do the other things he really loves to do.” Several people commented on the link between longer work hours and consumerism. One man said, “I was getting along real good, so there was no use in me working any more time than I had to.” He added, “Everybody thought they were going to get rich when they got that eight-hour deal and it really didn’t make a big difference. . . . Some went out and bought automobiles right quick and they didn’t gain much on that because the car took the extra money they had.” The mavericks, well aware that longer work hours meant fewer jobs, called those who wanted eight-hour shifts plus overtime “work hogs.” “Kellogg’s was laying off people,” one woman commented, “while some of the men were working really fantastic amounts of overtime—that’s just not fair.” Another quoted the historian Arnold Toynbee, who said, “We will either share the work, or take care of people who don’t have work.” PEOPLE IN THE DEPRESSION-WRACKED 1930s, with what seems to us today to be a very low level of material goods, readily chose fewer work hours for the same reasons as some of their children and grandchildren did in the 1980s: to have more time for themselves and their families. We could, as a society, make a similar choice today. But we cannot do it as individuals. The mavericks at Kellogg held out against company and social pressure for years, but in the end the marketplace didn’t offer them a choice to work less and consume less. The reason is simple: that choice is at odds with the foundations of the marketplace itself—at least as it is currently constructed. The men and women who masterminded the creation of the consumerist society understood that theirs was a political undertaking, and it will take a powerful political movement to change course today. Bernays’s version of a “democratic society,” in which political decisions are marketed to consumers, has many modern proponents. Consider a comment by Andrew Card, George W. Bush’s former chief of staff. When asked why the administration waited several months before making its case for war against Iraq, Card replied, “You don’t roll out a new product in August.” And in 2004, one of the leading legal theorists in the United States, federal judge Richard Posner, declared that “representative democracy . . . involves a division between rulers and ruled,” with the former being “a governing class,” and the rest of us exercising a form of “consumer sovereignty” in the political sphere with “the power not to buy a particular product, a power to choose though not to create.” Sometimes an even more blatant antidemocratic stance appears in the working papers of elite think tanks. One such example is the prominent Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington’s 1975 contribution to a Trilateral Commission report on “The Crisis of Democracy.” Huntington warns against an “excess of democracy,” declaring that “a democratic political system usually requires some measure of apathy and noninvolvement on the part of some individuals and groups.” Huntington notes that “marginal social groups, as in the case of the blacks, are now becoming full participants in the political system” and thus present the “danger of overloading the political system” and undermining its authority. According to this elite view, the people are too unstable and ignorant for self-rule. “Commoners,” who are viewed as factors of production at work and as consumers at home, must adhere to their proper roles in order to maintain social stability. Posner, for example, disparaged a proposal for a national day of deliberation as “a small but not trivial reduction in the amount of productive work.” Thus he appears to be an ideological descendant of the business leader who warned that relaxing the imperative for “more work and better work” breeds “radicalism.” As far back as 1835, Boston workingmen striking for shorter hours declared that they needed time away from work to be good citizens: “We have rights, and we have duties to perform as American citizens and members of society.” As those workers well understood, any meaningful democracy requires citizens who are empowered to create and re-create their government, rather than a mass of marginalized voters who merely choose from what is offered by an “invisible” government. Citizenship requires a commitment of time and attention, a commitment people cannot make if they are lost to themselves in an ever-accelerating cycle of work and consumption. We can break that cycle by turning off our machines when they have created enough of what we need. Doing so will give us an opportunity to re-create the kind of healthy communities that were beginning to emerge with Kellogg’s six-hour day, communities in which human welfare is the overriding concern rather than subservience to machines and those who own them. We can create a society where people have time to play together as well as work together, time to act politically in their common interests, and time even to argue over what those common interests might be. That fertile mix of human relationships is necessary for healthy human societies, which in turn are necessary for sustaining a healthy planet. If we want to save the Earth, we must also save ourselves from ourselves. We can start by sharing the work and the wealth. We may just find that there is plenty of both to go around. Jeffrey Kaplan has long been an activist in the Bay Area. His articles have appeared in various publications, including Yes!and the Chicago Tribune.  A Palestinian boy arrested by Israeli soldiers. Monday, November 19, 2012 By Barry Healy Soldaten, On Fighting, Killing & Dying: The Secret WWII Transcripts of German POWs By Sonke Neitzel & Harald Welzer Scribe Publications, 2012 448pp, $22.99 Our Harsh Logic, Israeli Soldiers Testimonies from the Occupies Territories, 2000-2010 Compiled by Breaking the Silence Scribe Publications, 2012 400pp, $22.99 There is unmitigated evil in both these books ― cruelty, violence, criminal’s countries. The fact that the awful truth comes out of the mouths of the perpetrators makes it all the more shocking. During world War II, the Allies bugged the private quarters of German prisoners of war to obtain intelligence. The records were buried deep in official archives until discovered by historian Sonke Neitzel in 2001. At least 100,000 pages of transcripts are analysed by Neitzel and social psychologist Harald Wetzer in a new book. From the very start it is shocking. If ever there was a myth that during WWII Nazi crimes were the preserve of the SS, not the Wehrmacht, it does not withstand one page of reading here. In one casual conversation after another the POWs talk freely of rape, murdering civilians, participating in mass killings of Jews, the deliberate mass starvation of Red Army prisoners, looting and more. The authors situate all these conversations in a psychological/sociological analysis of the conceptual “frames of reference” that these men inhabited: army discipline, the social bonding of a fighting unit and the warped reality created by Nazi propaganda, among others. Other frames of reference were the different experiences of air force pilots killing at a distance, U-boat crew who did not even see the people they killed, and front line soldiers who experienced death and killing at first hand. Neitzel and Wetzer’s approach is academically valid, but it is depoliticising and oddly dehumanising. When your hands shake with rage while reading about the senseless killing of civilians or the methodical sexual exploitation ― followed by murder ― of Jewish women, theoretical sociology just does not cut the mustard. The criminal role of Stalin’s inanely sectarian policies and the cowardice of the Social Democrats in delivering the German working class into the hands of Hitler is also outside Neitzel and Wetzer’s “frame of reference”. Once ensconced in power, Nazi social regimentation of the politically abandoned workers created the mentality required for the mass slaughter of WWII. Did the perpetrators see themselves as evil? No, they were just doing what they were trained to do. Shooting civilians? Well, once they are dead they are “partisans”. As for Jews, it is clear that Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda had a big effect. Racism was like the air the soldiers breathed. Even when Jewish women were coerced into sex in the forlorn hope of saving their lives, the soldiers were afraid of being accused of sexual “racial crime”, not of rape! Is it different with the interviews collected by Breaking the Silence, the Israeli organisation dedicated to getting the truth out about the Israeli Defence Force’s brutal occupation of the Palestinian Territories? In part, yes, but unfortunately, not enough. Unlike Soldaten, Our Harsh Logic, made up of transcripts of IDF front line soldiers, contains no stories of rape and sexual exploitation. Also, there are some accounts of soldiers arguing against offensive orders. For such small mercies we should be grateful, but it is insufficient. When I received the book, I started opening it at random and discovered to my horror comparable crimes to those in Soldaten, and a similar mindset. I inserted bookmarks at particularly awful accounts, but soon the whole book was filled with bits of torn paper. In Soldaten a German soldier recounts when a Pole accidentally bumped into him on the street and immediately the soldier bashed him to the ground. An IDF soldier similarly recalls: “We’d go out on patrol, here’s an example, some kid would just look at us like this, and we didn’t like the look of it ― so he’d immediately get hit.” On and on it goes for page after distressing page: kidnapping or killing “suspects”, killing people who happen to be sitting, unarmed on a rooftop (defined as a “lookout”), throwing stun grenades to keep people from sleeping as a psychological tactic and entering homes and smashing families’ belongings just for the hell of it. The official Israeli line on arresting a suspect is to say “Waqf [stop] or I’ll shoot”, followed by shooting in the air. The reality as told here is: “If he doesn’t stop and put his hands up in the second when you yell waqf, then you shoot to kill.” A soldier says: “We’d beat up Arabs all the time, nothing special. Just to pass the time.” “I hated them,” says another soldier. “I was such a racist there, as well, I was so angry at them for their filth, their misery, the whole fucking situation.” Stories of administering checkpoints show the arbitrary bureaucracy of judging who has the right to cross the apartheid lines that Israel has imposed, and who does not. Such is the “banality of evil”, as Hannah Arendt said in describing Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, whose approach to the Holocaust was that of a good bureaucrat. The lesson of Nazi Germany, reflected in Soldaten, is that fascism must never again be allowed to flourish. The message of Israeli oppression of Palestine is that injustice, wherever it is perpetrated must be contested. Former Israeli paratrooper Avner Gvaryahu, now an activist with Breaking The Silence explains to Green Left Weekly's Peter Boyle how 850 former Israeli soldiers have given testimony about the gross injustices against the Palestinian people they have witnessed and made to participate in as part of Israel's military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. He was visiting Australia to promote the book "Our Harsh Logic" (Scribe Publications). Disclaimer - I am posting this article because it has useful information which needs to be shared to assist in freeing the minds of visitors to this website. Having said that, I do not support all of the terminology used in the article (heaven, god, etc..). Take what resonates with you, and leave the rest.

Monday, November 12, 2012 by Mike Adams, the Health Ranger Editor of NaturalNews.com (NaturalNews) There's a secret that's much bigger than politics, health freedom, science or even the entire history of the human race. That secret remains entirely unacknowledged -- even condemned -- by the scientific community, and yet it is the single most important secret about everything that is. Yes, everything. That secret is simply this: We all survive the physical death of our bodies. Our consciousness lives on, and upon our death in this Earthly dream, our consciousness transcends this physical reality and experiences an existence so amazing and powerful that the human language cannot even begin to describe it. This is the message from Dr. Eben Alexander, author of the newly-published book, "Proof of Heaven." I recently read the book and found it both fascinating and also confirming of several important theories I've been developing about the nature of life and the Creator. A lifelong science skeptic who never believed in God, Heaven or consciousnessLong before this book was ever written, Dr. Alexander was a practicing neurosurgeon and a lifelong "science skeptic." He did not believe in consciousness, free will or the existence of a non-physical spirit. Trained in western medical school and surrounded by medical colleagues who are deeply invested in the materialism view of the universe, Dr. Alexander believed that so-called "consciousness" was only an illusion created by the biochemical functioning of the brain. This is a view held by virtually all of today's mainstream scientists, including physicists like Stephen Hawking who say that human beings are nothing more than "biological robots" with no consciousness and no free will. Dr. Alexander would have held this view to his own death bed had it not been for his experiencing an event so bizarre and miraculous that it defies all conventional scientific explanation: Dr. Alexander "died" for seven days and experienced a vivid journey into the afterlife. He then returned to his physical body, experienced a miraculous healing, and went on to write the book "Proof of Heaven." E.coli infection eats his brainIt all started when e.coli bacteria infected Dr. Alexander's spinal fluid and outer cerebrum. The e.coli began to literally eat his brain away, and he went into an extremely violent fit of seizures, verbal outbursts and muscular spasms before lapsing into a brain-dead coma. In this coma, he showed zero higher brain activity and was only kept alive via a respirator and IV fluids. The attending physicians soon concluded that Dr. Alexander would die within a matter of days, and that even if he lived, he would be a non-functioning "vegetable" with limited brain function. Statistically, the death rate for patients with e.coli infections of the brain is 97%. But here's the real shocker in all this: Rather than experiencing nothingness during these seven earth-days of unconsciousness, Dr. Alexander found himself "awakening" from the dream of his earthly life, suddenly experiencing an incomprehensibly vast expansion of his consciousness in the afterlife. This experience is described in more detail in his book "Proof of Heaven," but here are the highlights: • The experience of the afterlife was so "real" and expansive that the experience of living as a human on Earth seemed like an artificial dream by comparison. • There was no time dimension in the afterlife. Time did not "flow" as it does in our universe. An instant could seem like eternity, and consciousness could move through what we perceive to be time without effort. (This idea that all time exists simultaneously has enormous implications in understanding the nature of free will and the multiverse, along with the apparent flow of time experienced by our consciousness in this realm.) • The fabric of the afterlife was pure LOVE. Love dominated the afterlife to such a huge degree that the overall presence of evil was infinitesimally small. • In the afterlife, all communication was telepathic. There was no need for spoken words, nor even any separation between the self and everything else happening around you. • The moment you asked a question in your mind, the answers were immediately apparent in breathtaking depth and detail. There was no "unknown" and the mere asking of a question was instantly accompanied by the appearance of its answers. • There also exists a literal Hell, which was described by Dr. Alexander as a place buried underground, with gnarled tree roots and demonic faces and never-ending torment. Dr. Alexander was rescued from this place by angelic beings and transported to Heaven. God acknowledges the existence of the multiverseThe passage of "Proof of Heaven" I found most interesting is found on page 48, where Dr. Alexander says: Through the Orb, [God] told me that there is not one universe but many -- in fact, more than I could conceive -- but that love lay at the center of them all. Evil was present in all the other universes as well, but only in the tiniest trace amounts. Evil was necessary because without it free will was impossible, and without free will there could be no growth -- no forward movement, no chance for us to become what God longed for us to be. Horrible and all-powerful as evil sometimes seemed to be in a world like ours, in the larger picture love was overwhelmingly dominant, and it would ultimately be triumphant. This passage struck an important cord with me, as I have long believed our universe was created by the Creator as just one of an infinite number of other universes, each with variations on life and the laws of physics. (Click here to read my writings on the Higgs Boson particle, consciousness and the multiverse.) What Dr. Alexander's quote confirms is that our life on planet Earth is a "test" of personal growth, and that the way to make progress in this test is to overcome evil while spreading love and compassion. Even more, this passage also confirms the existence of free will and even helps answer the question I'm often asking myself: "Why are we placed here in a world of such evil and surrounded by ignorance, darkness and deception?" The answer appears to be that Earth is a testing ground for souls that have been selected by the Creator for the ultimate test of good versus evil. Earth as a testing groundAlthough "Proof of Heaven" doesn't go as far as I'm explaining here, my working theory is that our planet Earth is among the highest evil-infested realms in the grand multiverse. Only the most courageous souls agree to come to Earth by being born into human bodies and stripped of their memories. From there, the challenge of life is multi-faceted: 1) Figure out WHO you are and WHY you are here. 2) Learn to recognize and overcome EVIL (tyranny, slavery, oppression, Big Government, etc.). 3) Learn to spread love, compassion, healing and knowledge. Upon our death, we are judged by a higher power, and that judgment takes into account our performance in these areas. Did we achieve a measure of self-awareness? Did we work to overcome evil? Did we express love and compassion and help uplift others with knowledge and awareness? As you've probably already figured out, the vast majority of humans fail these tests. They die as bitter, selfish, substance-addicted, greed-driven minions of evil who mistakenly thought they were winning the game of life while, in reality, they were losing the far more important test of the Creator. The most important part about living a human life is not acquiring money, or fame, or power over others but rather achieving a high "score" in this simulation known as "life" by resisting evil, spreading love and expanding awareness of that which is true. For those who respect life, who practice humility and self awareness, who seek to spread knowledge and wisdom while resisting tyranny, oppression, ignorance and evil, their souls will, I believe, be selected for special tasks in the greater multiverse. That's the "real" existence. This Earthly life is only a dream-like simulation where your soul interfaces with the crude biology of our planet for a very short time span that's actually the blink of an eye in the larger picture. In reality, you are much more than your body. In fact, your soul is infinitely more aware, intelligent and creative than what can be experienced or expressed through the brain of a human. Trying to experience the full reality of what you are through the limited physical brain matter of a human being is a lot like trying to teach an insect to compose music like Mozart. The multiverse is teeming with intelligent life, including multidimensional beingsDr. Alexander's journey also confirms the existence of intelligent life far beyond Earth. As he explains in Proof of Heaven: I saw the abundance of life throughout the countless universes, including some whose intelligence was advanced far beyond that of humanity. I saw that there are countless higher dimensions, but that the only way to know these dimensions is to enter and experience them directly. They cannot be known, or understood, from lower dimensional space. From those higher worlds one could access any time or place in our world. This not only confirms the existence of other intelligent civilizations throughout our known universe, but more importantly the existence of multidimensional beings who can come and go from our realm as they please. Throughout the cultures of the world, there are countless accounts of advanced beings visiting Earth, transferring technology to ancient Earth civilizations, and possibly even interbreeding with early humans. Even the very basis of Christianity begins with the idea that an omnipresent multidimensional being (God) can intervene at will, and can therefore transcend time and space. Alternative researchers like David Icke also talk about multidimensional beings visiting Earth and infecting the planet with great evil. According to Icke, the globalist controllers of our planet are literally reptilian shape-shifters who have invaded our world for the purpose of controlling and enslaving humanity. Although nothing like this is covered in Dr. Alexander's book, it is not inconsistent with what Dr. Alexander was told by God during his coma... Namely, that there are multidimensional realities, that certain high-vibration beings can traverse those realities at will, and that Earth is infested with a great evil with the specific purpose of testing our character. If all this sounds a little too spooky for you, consider the words of the Bible itself: An upright talking reptilian snake spoke in audible words to Adam and Even in the Garden of Eden, did it not? The science skeptics are wrong (again)Regardless of what you might think about multidimensional beings, intelligent life beyond Earth, and the existence of great evil on our planet, there's one aspect of all this that's crystal clear: The science skeptics are dead wrong. Science "skeptics" are actually misnamed. They aren't skeptical at all. They simply follow their own religion with its own sacred beliefs that cannot be questioned... ever! Those beliefs include the utter worship of the materialistic view of the universe. Simultaneously, so-called "skeptics" do not believe they are conscious beings themselves because they believe consciousness is merely an "artifact" of biochemical brain function. There is no afterlife, they insist. There is no mind-body medicine, the placebo effect is useless, and there's no such thing as premonition, remote viewing or psychic phenomena. Oh yes, and they also insist that injecting yourself with mercury, MSG and formaldehyde via vaccines is actually good for you, that fluoride chemicals are good for the public health and that we should all eat more GMOs, pesticides and synthetic chemicals. It's no surprise these religious cult members of the "scientism" cult don't believe in an afterlife. That's what allows them to commit genocidal crimes against the human race today via GMOs, experimental medicine, toxic vaccines and other deadly pursuits. In their view, humans have no souls so killing them is of no consequence. As Dr. Alexander says, Certain members of the scientific community, who are pledged to the materialistic worldview, have insisted again and again that science and spirituality cannot coexist. They are mistaken. Well of course they are. The "science skeptics" are dead wrong about almost everything they claim to advocate. But their biggest mistake of all is in denying the existence of their own souls. Needless to say, they are all going to fail the human experience simulation once they pass on and face judgment. My, what a surprise that will be for those sad souls when they day arrives... I would hate to face God one day after having lived a life of a science skeptic, and then have God ask the question: "You doubted ME?" How could anyone take a look at the world around them and not see the signs of an intelligent Creator? Even the very laws of physics have been tweaked and fine-tuned in precisely the right balance so that our universe itself can support the formation of stars, and planets, and carbon-based life forms. This is called the "Goldilocks Enigma," and there's a wonderful book by that same name written by Paul Davies. No biochemical explanation for Dr. Alexander's experienceFor those skeptics who may be reading this, Dr. Alexander goes through nine possible biochemical hypotheses for his experiences and then meticulously and scientifically dismisses them all one by one. The result? His experience was REAL. In fact, it was "more real" than life as a human being. Remember, Dr. Alexander is a neurosurgeon. This guy knows the physical brain like no one else. The nine medical explanations he considers and dismisses as possible causes for his experience are: 1) Primitive brainstem program. 2) Distorted recall of memories from the limbic system. 3) Endogenous glutamate blockade with excitotoxicity. 4) DMT dump. 5) Isolated preservation of cortical regions of the brain. 6) Loss of inhibitory neurons leading to highly levels of activity among excitatory neuronal networks to generate an apparent "ultra-reality." 7) Activation of thalamus, basal ganglia and brainstorm to create a hyper-reality experience. 8) Reboot phenomenon. 9) Unusual memory generation through archaic visual pathways. Dr. Alexander may be the most credible afterlife witness in the history of humanityDr. Alexander's experience (and subsequent book) is arguably the best-documented case of the afterlife that exists in western science today. The fact that a vivid, hyper-real afterlife was experienced by a science skeptic materialistic brain surgeon who didn't believe in the afterlife -- and who subsequently found the courage to document his experiences and publish them in a book -- adds irrefutable credibility to the experience. This was not some kook seeking fame on a TV show. In fact, his writing this book earned him endless ridicule from his former "scientific" colleagues. There was every reason to NOT write this book. Only by the grace of God was Dr. Alexander healed of his e.coli infection, restored to normal brain function, and granted the VISION of the afterlife so that he could return to this realm and attempt to put it into words. Personally, I believe Dr. Alexander, and his experience mirrors that of countless others, across every culture, who have reported similar NDEs (Near Death Experiences). There is life after life, and the shift in consciousness of Earthlings that is required to take our species to a higher level of understanding begins, I believe, with embracing the truth of the immortality of our own souls (and the existence of a grand Creator). What does it all mean?Dr. Alexander's spiritual journey gives us a wealth of information that can help provide meaning and purpose in our daily lives. For starters, it means that all our actions are recorded in the cosmos and that there are no secrets in the larger scope of things. You cannot secretly screw somebody over here on Earth and think it won't be recorded on your soul forever. It also means that all our actions will be accounted for in the afterlife. If this message sounds familiar, that's because an identical idea is the pillar of every major world religion, including Christianity. It also means there are people living today on this planet whose souls will literally burn in eternal Hell. There are others whose souls, like Dr. Alexander, will be lifted into Heaven and shown a greater reality. What we choose to do with our lives each and every day determines which path our souls will take after the passing of our physical bodies. What matters, then, is not whether you actually succeed in defeating evil here on Earth, but rather the nature of your character that emerges from all the challenges and tribulations you face. This is all a test, get it? That's why life seems to suck sometimes. It's not a panacea; it's a testing ground for the most courageous souls of all -- those who wish to enter the realm of great evil and hope they can rise above it before the end of their human lifespan. About the author: Mike Adams is an award-winning journalist and holistic nutritionist with a passion for sharing empowering information to help improve personal and planetary health He has authored more than 1,800 articles and dozens of reports, guides and interviews on natural health topics, and he has published numerous courses on preparedness and survival, includingfinancial preparedness, emergency food supplies, urban survival and tactical self-defense. Adams is a trusted, independent journalist who receives no money or promotional fees whatsoever to write about other companies' products. In 2010, Adams created TV.NaturalNews.com, a natural living video sharing site featuring thousands of user videos on foods, fitness, green living and more. He also launched an online retailer of environmentally-friendly products (BetterLifeGoods.com) and uses a portion of its profits to help fund non-profit endeavors. He's also the founder of a well known HTML email software company whose 'Email Marketing Director' software currently runs the NaturalNews subscription database. Adams volunteers his time to serve as the executive director of the Consumer Wellness Center, a 501(c)3 non-profit organization, and regularly pursues cycling, nature photography, Capoeira and Pilates. Known by his callsign, the 'Health Ranger,' Adams posts his missions statements, health statistics and health photos at www.HealthRanger.org Learn more: http://www.naturalnews.com/037917_Proof_of_Heaven_afterlife_Creator.html#ixzz2C24Sb2Aa |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed